Previously on Nuclear Houseplant:

"I'm not the kind of person who's going to say that something like that is going to be a failure no matter what. But that's not to say that there's no such thing as hubris."

"'I just want to go crazy and shoot some shots that make me remember why movies are badass.'"

"His is not a delicate touch"

"Watchmen, the film, is pretty okay. And that's all."

"I assure you, I['ll] spoil the hell out of book and film."

Back in July 2008, when I tried to watch The Dark Knight with only moderate success, surprise! I got to see a trailer for the upcoming Watchmen movie. This was the first Watchmen theatrical trailer, and maybe it's because I'm cynical and jaded, but I was underwhelmed. Of course, I was sitting next to a man—a grown man—who hooted gleefully after the trailer and also every few seconds during the armored car chase scene in the feature. Gleeful hooting didn't seem like the right response to Watchmen, somehow, especially not when, in typical Hollywood fashion, all the trailer gave us was mind-numbing visual stimulation, most of which was unrepresentative of the chatty-kathy graphic novel I'd read. The trailer also had one of those crazy things Rorschach's always saying, delivered without the ironic detachment Alan Moore uses, seeing as how he's not, you know, a psychotic fascist. I mean, maybe it was just that hooty guy's fault I didn't like the trailer, but I don't really think so.

I'll concede that there was some (scant) reason to hope. Strangely, the Watchmen trailer featured the The Smashing Pumpkins song "The Beginning is the End is the Beginning," the slower variation of "The End is the Beginning is the End," which was the Batman & Robin music video that was all over MTV during the summer of 1997. I thought this was probably just a really, really unfortunate music selection, but I was also hopeful: maybe it was actually a brilliantly self-conscious gesture at satire, a sort of subtle announcement that this was going to be the movie that once and for all broke the comic book movie mold and delivered on its promise. Watchmen was going to make everything else look like Batman & Robin! Something like that, anyway. There was also the sort of neat clock-like sound of the drum machine in the background of the song, which slows gradually, and continues to wind down, as the song (and trailer) ends. Just like Watchmen! It ends and doesn't end!

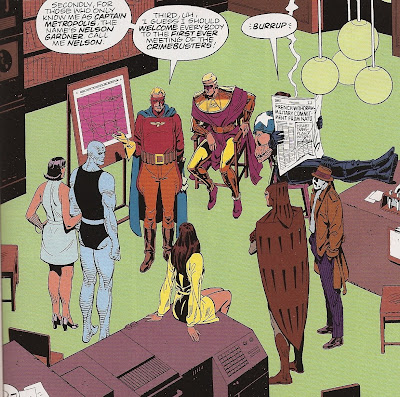

Mostly, though, I thought what I usually do when something I like is getting the movie treatment: this was going to be a bad Watchmen, watered down for mass audiences, robbed of its essential meaning, detoothed. A cinematic-commercial experience complete with Kubrick sets consisting of rapists and mass murderers (the guy in the middle's all right).

I sat back and waited for several months. "Waited" is too strong a word, honestly, because I didn't really think much about it.

Then the past couple of months rolled in, the Doomsday Clock advanced (not the real one, just a metaphorical one), and we were only a few weeks away from release! People started talking about Watchmen! Watchmen had become a title people knew! I can't remember now if it was around that time or when the Wired article hit, but at some point, I realized that Watchmen had miraculously gained a broader following over the past several months, on the strength of a few movie trailers, than it had done in the previous twenty years on the strength of, um, itself.

And that must explain why Alan Moore hates film adaptations.

That doesn't really matter, though. I said it in the previous part of this thing, and I'll say it again: when your work is published, it's no longer just yours. "Your work" may be broadly interpreted, too: cf. "WWJD?" (or, even more laughably, Lord's Gym) merchandise, Che Guevara stuff, and Charles Manson t-shirts, just to name a few. If you've produced, undergone, suffered, and/or done something significant, evil, fascinating, and/or tragic, you can and will be trivialized. Alan Moore's been in the line for some time now, because a respectable chunk of his copious corpus has been run through the machine, but it's a long, long line, and we are a people with an insatiable appetite.

At least he gets the satisfaction of knowing his predictions were vindicated. I mean, I guess that's one way of interpreting that picture.

All of this is just my attempt at putting up walls, shielding myself from any accusations of fanboyism. I'm not a fanboy; I don't owe Alan Moore a Wookiee life debt, and I'm not here to mourn how, oh, man! the greatest book of all time has been damaged by the predations of Hollywood. I do want to show you just a few of the ways the Watchmen movie misses the point of Watchmen, which is a pretty good book.

One important tool to have in the box when you read anything by Alan Moore is a sense of detachment. You'll be needing that for when Moore switches narrators on you, or when he has someone really unpleasant, possibly even unreliable, telling you what the world's like. In his review of Watchmen, Anthony Lane makes this observation:

You want to hear Moore’s attempt at urban jeremiad? “This awful city, it screams like an abattoir full of retarded children.” That line from the book may be meant as a punky retread of James Ellroy, but it sounds to me like a writer trying much, much too hard; either way, it makes it directly into the movie, as one of Rorschach’s voice-overs. (And still the adaptation won’t be slavish enough for some.)

I have to hand it to Anthony Lane: his harsh criticism of the book suggests he's actually read it, at least sort of, unlike the mass of critics who just give it high but generic praise. Take, for instance, Joe Morgenstern in the News Corporation's The Wall Street Journal: "The source material, a graphic novel by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, is a work of unusual intricacy, visual power and narrative ambition. Doing full justice to such a classic in a single movie was clearly impossible ..." I will give David Edelstein of New York Magazine credit, because he's clearly read the book, and he's aware that Rorschach is "a grotty right-wing nihilist in a stocking-cap mask." Probably we oughtn't confuse Moore's voice with Rorschach's. If you want Moore's voice, you might find it in this editorializing moment:

But maybe Lane's not deliberately confusing Rorschach's perspective with Moore's perspective, and if it's just Moore's prose that's on trial here, I'll be the first to admit that his writing is far, far from unassailable. What Lane does, though, is to attribute a sadistic quality to Moore that I think is misplaced:

The problem is that Snyder, following Moore, is so insanely aroused by the look of vengeance, and by the stylized application of physical power, that the film ends up twice as fascistic as the forces it wishes to lampoon. The result is perfectly calibrated for its target group: nobody over twenty-five could take any joy from the savagery that is fleshed out onscreen, just as nobody under eighteen should be allowed to witness it.

This is the line Lane takes with his mischaracterization of Moore, whom he also lumps in with the writers of those endless "shelves of cod mythology and rainy dystopias, patrolled by rock-jawed heroes and their melon-breasted sidekicks," who is the sort of satirist whose work "should meet the needs of any leering nineteen-year-old who believes that America is ruled by the military-industrial complex, and whose deepest fear—deeper even than that of meeting a woman who requests intelligent conversation—is that the Warren Commission may have been right all along."

I don't care about defending Moore, but I am outing Anthony Lane as a medium snob, right here, right now. The guy plainly hates comic books. Oh, sure, there are those "masterwork[s], such as 'Persepolis' or 'Maus,'" but up against those other shelves of crap, those sorts of books can only be the exception to the rule. If only we had someone with Lane's sophisticated tastes to save us from these purveyors of penny dreadfuls! "Incoherent, overblown, and grimy with misogyny, Watchmen marks the final demolition of the comic strip, and it leaves you wondering: where did the comedy go?" Let me reiterate: Anthony Lane read Watchmen, no question. His editor asked him to read it, or perhaps he selflessly took it upon himself as research for his review. He read it perfunctorily, at least its first five or ten pages, and he resented every minute of it. Maybe if it'd been more like Snuffy Smith, he'd have enjoyed himself.

The larger problem, to get away from his disdain for this still ghettoized medium, is that Lane is also transparently conflating Watchmen, the book, with the new movie. They really aren't the same thing. I just mentioned Lane's imputation of a sadistic quality to Moore. It really isn't there. I can't blame anyone for seeing it in the movie, though; I certainly did. As Karen Green pointed out in a recent installment of her ComiXology column, the violence of a comic book movie, particularly a comic book movie that's based on a violent comic book, is inevitably going to be greater than the violence in the original work. Karen paraphrases Scott McCloud: "much of the action occurs in the interstices, and we complete the snapshot captures of the action, letting our brains fill in the balance." The representation on screen of that frame-by-frame violence proceeds at a pace and for a duration over which we have no control, unlike with a comic book, and there are the added problems of motion, sound, and audience to consider. The art style of Watchmen the book is also consistent with other comic books of the eighties or, for that matter, the sixties. Not to say that Dave Gibbons' work isn't distinguished, but the colors in particular are relatively bright, and the overall presentation makes the scenes of bloodshed disturbing without being physically sickening. The conversion to live action inevitably makes the violence and the gore more affecting, even when the blood in the movie looks more like some sort of black ichor than blood (and yes, colorlessness in the movie is a frequent annoyance).

I'm not a squeamish viewer, and I've watched (and enjoyed) many films where I know the violence was excessive in some sense. This can be a legitimate aesthetic choice, as it often is. But the representation of graphic violence in film is always at least a bit problematic, because, again, unlike comic books, where the reader doesn't have to endure the violence for any length of time, a movie creates a situation where the viewer is wrapped up in the violence, is in some ways even complicit with it, and is certainly invited to respond to it. There is graphic violence in both versions of Watchmen, but Alan Moore presents the violence and the bloodshed in his book with characteristic detachment. He isn't callous or unconcerned; he simply shows the violence, and that's all. Zack Snyder is the sort of director who, with no real artistic reason that I can discern, lavishes attention on bloodshed, slowing it down and lingering over it.

And he actually enhances the violence: you may remember the scene in the book where Rorschach chains the pedophile/murderer to a stove, throws him a hacksaw, and then douses the man's house in kerosene and leaves him to determine his fate. It's a dark scene (in fact, it's made clear in the book that this is the scene where Rorschach "snaps"), but it's harder to take in the movie. There, Rorschach tells the man, who's just asked to be turned over to the authorities and given "help," that people receive the benefit of imprisonment, and animals have to be put down. Then he takes a cleaver which he embeds in the man's head, several times, right before our eyes. Aside from the charming observation, not in the book (there, Rorschach makes comments that implicitly connect himself, as a member of humanity, to the pedophile), there's this prurient fascination with the act of killing. It comes out in the scene where Rorschach throws hot fryer oil on a fellow prisoner, whom we watch as he screams and melts for several seconds. Rorschach shouts that it isn't he who's locked in with the prisoners, but they who are locked in with him. In the book, he states this coldly, and the line appears in a caption, reported via secondary narration, divorced from its context. Every aspect of the book's presentation at this point invites a cool appraisal of these events. I'm sorry to say, though, that the audience at the viewing of Watchmen I attended actually cheered for Rorschach. It reminded me of Sin City a few years before; my audience at that film really loved the scene where Hartigan dismembers Elijah Wood and ties him to a tree to be devoured by dogs.

That's what I think is wrong with Snyder's handling of violent scenes. I don't in the least mind violence in movies, but I think there are inherently distasteful ways of dealing with it, or there are ways that invite your audience not just to respond to it in a strong way, which is a good thing, but to enjoy it, which I find troubling. And maybe that's the kind of challenging content you'd expect from a really artistic film, but Zack Snyder is not that director, and Watchmen is not that film, certainly not this Watchmen.

A frequent critique of the film is that it's imitative of the original to a fault. If only! The direction, the composition of the film, is like amateur hour compared to the deliberate and in fact meaningful framing of the story in the book. I realize this is a long post already, so I'll only focus on a couple of examples. First of all, Watchmen is almost a textbook in how to exploit the possibilities of the comic book medium. The themes of simultaneity—of non-linear time, of time being lost and time being stopped and time running out—and of interconnection run throughout the book and intertwine at points, and there is simply no more appropriate medium to present this, that I can think of, than a comic book. As (again) David Edelstein observes, "Reading Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’s splashy, blood-drenched superhero graphic novel Watchmen is a delirious experience—the eye races forward, circles back, and darts around the panels while the brain labors to synthesize the data." Comic books offer the possibility of this studious reading, re-reading, and what? de-reading? Time is effectively negated, and the reader can flip backwards or look up or to the left at another panel, and even if the reader has no desire to do that, there are a few occasions where Moore and Gibbons do it for her by recycling old panels and jumbling them into a confused mess. Dr. Manhattan laments the fact that Laurie Juspeczyk can't see time as he can, but we do. This is what I think Brian K. Vaughan, in his quote from the Wired article, means when he says, "The medium is the message." Taking Watchmen out of its native medium was a risky decision artistically, and no attempt has been made to adapt its central conceits, so perfectly fitted to that medium, to its new celluloid context. This slavish imitation critics are referring to is a hoax: Watchmen, the movie, if it did what it already does quite a bit better, would be like one of those child prodigies who can play Mozart flawlessly. The notes are right, but the music isn't there. There's just something to be said for the appreciation and the discernment that can only come with experience, and that's the quality most obviously missing from Snyder's adaptation.

On the contrary, I talked yesterday about the glaring immaturity of many of Snyder's insertions, particularly the music, and I won't elaborate further. Well ... I'm trying to resist ... okay, some of the imagery is almost irresponsible. I thought the graphic reenactment of the JFK assassination was pretty indulgent, for instance.

Speaking of imagery, there really isn't much in this film. There are a few clocks. Okay. There aren't enough to convey the importance of time in the story: time running out on the Doomsday Clock, time suspended from Dr. Manhattan's perspective, time as sort of a canvas for the narrative, all of that. There also aren't enough to tie scenes together visually, and there aren't enough to provide the sort of seamless transitions that occur throughout the book. This is another thing the book does brilliantly, and it wouldn't have been difficult for film to follow suit. There are constant shifts between completely different scenes in the book that are facilitated and smoothed with clever transitions. A shark's head in the pirate story (axed, but coming out on DVD soon!!) becomes a pink triangle on a poster for a lesbian political group. A field of stars becomes a collection of watch gears arrayed on a black cloth. Even in the few instances where the film does take these transitions from the book, they're poorly done: the ink blot that turns into Rorschach's mother and her john bears no resemblance to the latter image because of the way the framing's mishandled.

I never meant to make this survey exhaustive, and now I'm realizing that I could criticize the movie for several more paragraphs, so I'll call it a day here. I don't mean to say that this is a truly awful movie. I'm fairly sure it's not a good movie, especially not in comparison to the book (in the absence of it it would be much better), but if you don't demand the thematic richness of the comic book, it should convey the material suitably for your needs. It would have been nice if the movie had played with its own medium the way the comic book does, and it's true that this is the latest in a long line of comic book movies, and the genre is ripe for some deconstruction of the sort Moore and Gibbons engage in in Watchmen, but that's not what this movie does. It's basically in line with the genre. Lots of action, if that's your thing. It's okay in its way, I suppose, but it definitely doesn't justify its existence, and it never seemed particularly necessary or even desirable.

That's my take. Call me a fanboy, but I think I've gone beyond nitpicking to show how Watchmen really is an inferior reproduction. I have no disrespect for anyone who enjoys it; I'm glad, personally, that I got to see it, because there is something there to like. It suffers from the comparison to its source, though, and not just in ways that don't matter.

I for one, found your long version a worth while read. I think that the movie can be enjoyed on its own merits and for its own sake. I enjoyed seeing the actors bring their characters from the printed page to life, so to speak.

ReplyDeleteSorry I'm just getting to this now, Jason. I think it's a terrific piece and I agree with it as much as I can, ethically, not having seen the film.

ReplyDeleteBrian Wood twittered, I think, about that moment with the kerosene, and how horrified he was at the audience at his screening cheering it. It appears to have been the same kind of moment, for many people, as lions tearing apart Christian in the Colosseum. Ah, well: if this isn't a time for comfort in bread and circuses, what is?

It is, perhaps, close-minded of me to say that this post confirms me in my desire not to see the film at all. Yeah, well, sue me. I was traumatized enough by Sin City, even while admiring the devoted capture of the comics' visual aesthetic.

And thanks for the cite--gosh! I was covered with blushes when I read that!

Sure enough, here's Brian's post:

ReplyDelete"The audience cheered when Rorshach killed the guy with hot oil. Really cheered. What's wrong with people?"

I'm glad I wasn't the only one who thought that was upsetting.

While I definitely enjoyed the movie to some degree, and it was nice to see the characters brought to life, like pfong says, I will acknowledge that it's not for everyone, and to me it didn't feel necessary. It's one person's version of the book, and that's fine, but it isn't definitive--thank goodness.

Jason,

ReplyDeleteI generally agree with your post--actually, I think you caught many of the flaws of the film pretty well. And as always, I really appreciate the thoughtfulness and character of your writing--your critique highlighted many an element that I missed when wat... viewing the movie. I did enjoy the film, although not near as much as I hoped I would. I really wanted to disagree with you on your review, but I can't.

You're probably right about the excessive graphic violence of movie. I came about looking at it differently. I sort of felt that the graphic violence was put in to justify the R rating, which was necessary to show Dr. Manhattan properly detached. It became a sort of inside joke--letting the aggressive, early-twenties man in the audience tell himself the movie's rating was just for gore, not the chance to see a giant blue phallus. Of course, seeing the director's previous body of work, your explanation makes more sense.

More substantively, I was most disappointed with the alterations to Rorschach's story. I've always loved Rorschach. (I disagree with your terming him a fascist--he never seemed able to work well enough with others to be a fascist, unlike, say, the Comedian.) I feel that the movie tried to make Rorschach into a standard Wolverine/Punisher anti-hero type, and it missed the most endearing aspects of his character. The difference between Rorschach hacking a criminal and Rorschach walking out with the place on fire is not as subtle as this movie wants to think it is, and I think you did a masterful job of the movie fails there. The movie also missed Rorschach's act of mercy for the young child, and it changed the nature of his sacrifice. It seems like R.'s line in the trailer, the "I'll look down and say, 'No,'" became the driving motive, rather than his inability to accept any moral ambiguity. Maybe a minor point, but to me that's what hurt the most.

If you really wanted to stretch to find a moral, turning Watchmen--with its infinite shades of gray--into a standard superhero movie with easy black and white answers is perhaps an amazing act of satire. Probably not, but there must be a pony here somewhere!

I do think the movie brought one benefit. If helped show the "masks" as much more detached--I felt a certain loneliness, and a distance between them the regular persons that I missed in the book. Now, this would be a tragedy if it was seen without the comic as a counter. And perhaps it's another reason why the movie is less than impressive, because by taking out the vignettes of human interaction it makes Watchmen even more of a standard hero movie. Still, the movie helped bring out several themes in the comic by serving as a nice contrast.

Which shouldn't be the best thing one can say about it.